Anna Frants and Marina Koldobskaya are cofounders of the Media Lab CYLAND that provides creative technical needs (from any kind of equipment to the services of computer programmers) for art ideas. Since 2007, they have held the festival of media art CYFEST: started in St.Petersburg, now it is completely delocalized and, this year, it takes place in St. Petersburg, Moscow, Berlin, New York and Tokyo as well as on the internet. Anna Matveyeva talked with the festival founders about media, globalization and about the fact why the spiritual bonds do not work.

Anna Matveyeva: How did the story of the CYFEST Festival began?

Anna Frants: We were interested in uniting the realm of art with the realm of technologies. In Russia, such events are extremely rare: the Yota Festival was held a couple of times; the exhibit Lexus Hybrid Art has been organized annually in Moscow. In our practice, we make an emphasis on art: it is ultimate, and technologies are attached to it only as a tool.

Marina Koldobskaya: in 2007, when we just started, the vector of westernization and modernization had not been depleted yet. Innovating ideas were supported, though not with too much enthusiasm, and we had a nerve to create something which had never been before. After all, in Russia – in any event, in St. Petersburg – there was no stage for media arts, just random separate authors. We wanted to hand a set of tools to the artists, to help those who wanted to use new technologies, but didn’t know how. The thing is that the work of media art requires an effort not just from an artist, but also from engineers, computer programmers, videographers – long story short, trained professionals – moreover, the ones who understand what they are doing. One can’t take any office system admin and say, “Do me an artwork” – a person needs to understand what its meaning is. There aren’t many people like that and, much like in any new undertaking, they were gaining experiences together with us. It had its moments.

A.F.: We had a prototype – the organization E.A.T. (the lab Experiments in Art and Technology that collaborated with several generations of artists, from Jasper Johns and Andy Warhol to Irina Nakhova. – Artguide) that was created in the second half of the 1960s by the engineer Billy Klüver and the artist Robert Rauschenberg. Julie Martin, Billy Klüver’s widow, came to the first CYFEST in 2007 and gave a lecture about the history of this initiative.

A.M.: But now you are talking not so much about the festival as about the media lab CYLAND? After all, it was created precisely for the purpose of giving an artist an opportunity to come there with his own idea so that the lab would give him technological capabilities for its implementation.

M.K.: They came into being simultaneously, and the festival was conceived as the lab’s face. The work in art cannot be a thing in itself – one needs to demonstrate successes, to attract, to engage, to showcase and, to effect all this, one needs an event.

A.F.: In the long run, our festival has expanded to such an extent that now we are the largest not only in Russia, but also in the entire Eastern Europe.

M.K.: The media lab has been long functioning not just in Russia. This is an open international community of artists, and here we can draw a parallel with the Fluxus movement. CYLAND stands for “CYber isLAND” – this is a drifting island, the Swift’s Laputa of sorts, which floats on the airwaves and accumulates creative energies. In point of fact, any enthusiast from any country can join us – provided there is an access to the internet.

A.M.: Media art, strange as it may seem, is separate from all the rest of the world’s art. It has its own fashions, trends, stars as well as its own range of problems. A commonplace average art historian, who seems to be going to exhibitions and reading books on a regular basis, knows practically nothing about this world. This world is cut off by the information barrier from the general art process. In order to know about it, one needs to study it expressly. Why is it so?

M.K.: This is a question that I, as a curator, want to ask myself, as a critic! Why is there no discourse? Why is there no development of the critical instrumentarium or the language for an adequate description of media projects? What’s the problem? We, on our side, do insist that the technology is just the technology. Here is an artist, and if he needs a brush – all right, let there be a brush; if he needs a video projector – a video projector is what he’ll get; if he needs a device, a soft or a hard – we will try to arrange for it. However, to squeeze out a normal critical or at least descriptive text from art historians – this we fail to do. We fail to do this with Russian art historians altogether, and we get it from the Western ones with a really great difficulty. This goes both for specific artworks and for the event as a whole. There is nothing except for advertisement-announcement texts in the mould of “it’s blinking there, it’s sparkling here” that could be done by any garden-variety journalist.

A.F.: Apparently, it’s because technologies look intimidating, in particular, for art historians. But one shouldn’t be intimidated by them because they are just a material – much like photography and cinema were for art at the time. New technological capabilities and new tools come into being…

M.K.: But why – why does it look intimidating? Critics are ordinary contemporary people. They have computers, Smartphones, iPhones, iPads, data tablets, and they use them as everymen every day and all the time. But why are they afraid of them intellectually? This is a complete mystery to me. I myself didn’t know how to do anything in the media, and I still don’t know how

to program and nor am I a most advanced user, but I’ve had absolutely no difficulties with the curating of media-art exhibitions. If I don’t know something – I’ll ask. If I don’t know how to do something – a specifically trained person will come over and stick a needed wire into a needed jack. And critics don’t even need to do that. So why do they find it difficult? Yes, of course, the media art is a really huge world, and it has its own history, its own trends and its own heroes. Be it sound art or computer games or video – a wide array of various genres has been developed everywhere. It is clear that nobody can keep track of everything, but there is nothing essentially unfathomable in there. It can be unclear how it is done – so what? If a critic thinks that he understand how a picture is painted, then he is mistaken as well. The most important thing about a work of art is the thought and the sentiment, regardless of whether they are expressed with a pencil or a computer code. The critic’s job is to think it through and to evaluate.

Yes, of course, the media art is a really huge world, and it has its own history, its own trends and its own heroes. Be it sound art or computer games or video – a wide array of various genres has been developed everywhere. It is clear that nobody can keep track of everything, but there is nothing essentially unfathomable in there. It can be unclear how it is done – so what? If a critic thinks that he understand how a picture is painted, then he is mistaken as well. The most important thing about a work of art is the thought and the sentiment, regardless of whether they are expressed with a pencil or a computer code. The critic’s job is to think it through and to evaluate.

A.F.: Speaking of, this year in Tokyo we are going to have a very interesting project of Daniil Frants and the artist Ivan Govorkov. Daniil, my son, is our youngest – though merited – member of CYLAND: he has been conducting master classes for children since he was 12 years old. In this project, he plays the part of a programming DJ (there is not even such a term yet in the contemporary culture). As for Ivan Govorkov, he is an absolutely traditional artist – a draughtsman. He will be doing his drawings while the movement of his pencil will be read by the program of electronic sculpture that allows interactively to change the settings and then to be printed on a 3D printer and transformed into a sculpture. From the technology point of view, this is rather simple, and the entire process is more of a performance. And yet its origins lie in a traditional art form – the drawing – and it ends in a traditional art form – the sculpture.

A.M.: CYFEST began in 2007 as a Russian, or even a Saint-Petersburg initiative – I remember you guys speaking about this with pride. Nowadays, this is a geographically spread, global story that takes place simultaneously in numerous cities – and it is not really important, in which ones exactly, it is just that the initiative has become global. Such globalization – is it the private circumstances of CYFEST alone or is it an overall trend?

M.K.: The singularity of contemporary world is that it is changed not by the convulsions of politicians, but by the new devices that come into being every week. Our daily routine, behavior, thinking – everything changes all the time. We live in the stream of a mad buildup of the capabilities, and art cannot fail to interpret it. I myself am from the Paleolithic period because I still remember the time when articles were written by a ballpoint pen, when one would dictate to a typist over the phone: “Comma… dash…” Now it sounds like a joke, but twenty years ago, in order to send an urgent message to Germany, I would write the letter on a piece of paper, put it in an envelope, affix a German stamp that I had in store, go to the airport, find there some German guy with a kind face, hand him this letter and ask him to drop it into a mailbox at the airport. And now, if my computer freezes for five minutes I begin to bawl my head off: like, how can one possibly work with an internet like this, but I can’t download a video and so on. Current means of communication allow people who are sitting in Russia to see an exhibition that is held in Tokyo and, if everything is well organized, to see it quite adequately. Last year, we did a broadcast from Berlin: the person with a web cam was walking around the exhibition hall, and in St. Petersburg, at the Education Center of the Hermitage, students were observing not just the exhibition, but also the process of its mounting online. This year we want to repeat such a broadcast. The accessibility of any spot on the globe, ease of communication, travel speed and gigantic increasing volume of information – all these are the changes of a civilizational nature, and they increase exponentially. We have moved from an analog civilization into a digital one, and this requires some thinking through.

A.M.: Then how important it is for a curator to be physically, corporeally present at some spot? And how important is it for the artist and the spectator? If everything is virtual, why organize some exhibits on locations when everything can be done on-line and there is no need to sweat it with the exhibition halls?

M.K.: It can’t be done. I mean, it can, but this is not enough. It is mostly information that is transmitted over a distance, but art is also connected to the generation of emotions, including the ones at a level of bodily sensations. About fifteen years ago, there was a trend of the virtual bodily reality: everybody started making cyber helmets, gloves, video-goggles… There even

was an idea that, that’s it, there will no longer be love – everybody would be screwing via the computer. But it didn’t work! Human interaction remains the most important factor. CYFEST is to a great extent an educational event. Yes, a great deal can be seen, perceived and comprehended through recording and broadcasting, but this mainly concerns the viewer, the public. However, for the participants, the point of the festival is ultimately to get together and do something together.

A.M.: In this context, how important is the localization that you have foregone by making CYFEST not a Saint-Petersburg, Russian, German or Japanese event, but an event that simply exists in the global information field accessible to everyone regardless of the geographic belonging?

M.K.: It became clear a couple of years ago that the country started moving backwards. How long it is going to circle, hover and look for its special path is not clear, and the initial idea of a kickass Russian media event has become outdated. On the plus side, a different idea emerged: we can exist outside the geo referencing. This approach began to play out splendidly, and we decided to develop it: last year, the festival was held in Berlin and St. Petersburg. This year, there has been an addition of Moscow, Tokyo and New York. In the interim, in 2013, we organized in Venice the exhibition Capital of Nowhere that was held simultaneously with the biennale. Initially, we had qualms that we were taking coals to Newcastle and that our event would get lost in the city’s vibrant cultural life. It turned out that it was far from it! There was an evident interest in us.

A.F: We also started organizing traveling exhibitions. They have the same concept, but, depending on where they are going, they can change the lineup of artist, for instance, by engaging the local talents. The theme for this year is “The Other Home”. An exhibition under this title has already been held last summer in St. Petersburg as part of Manifesta in a small format, and now we are unfolding it into a big international event. Local artists get involved into the process, which is a positive thing. There is a difference between the localization and the provincialism; we try to be not provincial, but to maintain some roots. We engage a certain nucleus of the artists from St. Petersburg, and then other forces move in – for instance, Berliners when we are in Berlin.

A.M.: I adhere to the point of view that the language of contemporary art is fully international. Attempts to present something specifically Russian or something else along national lines always represent, in our day and age, either the colonial mentality or some savagery from the 19th century. But you, holding the festival in different countries, do you feel a request for the representation of specifically Russian art?

M.K.: The national art, the representation of national culture is not exactly a totally empty and idle undertaking. The process of forming of nations and, accordingly, of national cultures has not been completed yet – just look at the Eastern Europe for an example. However, to represent “things Russian” today is impossible because our identification is, in fact, lost – I hope, temporarily. I don’t understand what the contemporary Russia is in a cultural sense. There are many conflicting models – the imperial, the anti-imperial, the pro-Western, the pro-Soviet, the archaizing, the modernizing… I don’t see the common nucleus, the core, the cultural paradigm that could be represented. There was a time when there were roughened but still connected to the reality notions of, for instance, what the authority is, and there was intelligentsia that was erroneously considered to be anti-Soviet, though they varied greatly. One could produce either a Soviet culture or an anti-Soviet one – because any alternative looked as a protest. This aftermath was still in place for some time. Now, however, everything has fallen to pieces, and what the Russian culture is today – nobody, unfortunately, can tell. I say “unfortunately” because, in order for a country to exist, the common core is needed.

A.M.: I beg to differ, the spiritual bonds, in fact, is what now dumped on us in spades. It’s a different matter that they don’t work…

M.K.: You’ve just answered your own question. Spiritual bonds emerge when there is no core. When a construction is falling apart, one tries to keep it up with some bonds and braces. This never works for long. Therefore, if, in the Soviet times, there was a joke “Does the abroad exist?”, now, all joking aside, I ask a question, “Does Russia exist?” In a cultural sense – where is it? One could talk about some local stories, local tendencies, generations… Yes, whether we like it or not, we represent our generation, and we have a unique background, come to think of it. In a sense, we represent the Saint-Petersburg art – and, unlike Russia, I still understand what St. Petersburg is.

A.F.: For some reason, when it comes to American or English artists, there is never a question of whether they represent the American or English soul. I believe that the Moscow conceptualism played a special part in this matter. It became a recognizable brand. At any spot of the world, if you asked a person who has even a little interest in art, “What is Russian art?” he would instantly reply: “The Kabakovs”.

M.K.: As for us, it’s been over a long time ago. The Moscow conceptualism is a respectable brand indeed, but I have never been its fan. I was scared off by an excessive preoccupation with the authorities. It was hard to shake off the feeling that the majority of those artists, critics and curators were people who wanted to become bosses, big shots, but hadn’t managed to fit into the bureaucratic concept, so they moved in a roundabout way. The climate in St. Petersburg is different: our conceptualists steer clear of authoritative ambitions – they are mostly punking and fooling-for-god’s-sake. But if somebody decided to go into administration, he would understand that the game rules here are totally different in there. Coming back to the Moscow conceptualism – one looks at today’s exhibitions, and there is a feeling that this is some distant history, something archaic, belonging in a museum and long gone. Though, the authors – here they are, and some of them are not that old…

A.M.: Yes, Anna Frants has also just spoken about this: that this is a brand that we now officially represent.

A.F.: Vitaly Komar told me a wonderful phrase: “All my admirers believe that I am dead by now. I met a young lady, and she says: ‘This is you??? Oh! You are still alive???'”

M.K.: Komar and Melamid were really responding to the request of their era. But it’s already been two, three generations ago, there have been children and grandchildren since, but one still tries to squeeze something out of that brand. There is a German saying: “If you reheat soup too many times it will go bad”.

A.M.: Is there a request that CYFEST represent the precisely Russian… what? Something Russian. Or the art that you represent is viewed without referencing the point of origin – on an equal basis?

A.F.: I would say that no. Yes, we’ve come from Russia – this is clear from our accent, if from nothing else. But I can cite the American side as an example: after all, they have two of every sort over there. Everybody there came from somewhere, and everybody has an accent. A question like that doesn’t even come up.

M.K.: There is most likely a request, but, after all, we don’t have to respond to it. There is an advertizing campaign that precedes the festival, during which we by no means promise that we would be talking about the Russian soul, Russian politics and what troubles could be expected from us – after all, in reality, this is precisely what people want to hear! We are about something else. So it is clear for everyone right away that if they have come to us with a search for the “Russian soul” – they are barking up the wrong tree. On the whole, rumors about the world interest in the “Russian soul” are greatly exaggerated. I happened to come across the interest in “things Russian” among the leftist European academics – these extremely late children of 1968, madmen with burning eyes who believe in socialism… and in the fact that someone somewhere is in possession of the truth that is hidden from them. They are really tied up to the European anti-Americanism, and they are looking for a different footing somewhere outside. So, when they receive not the response that they expected, they get really miffed with us.

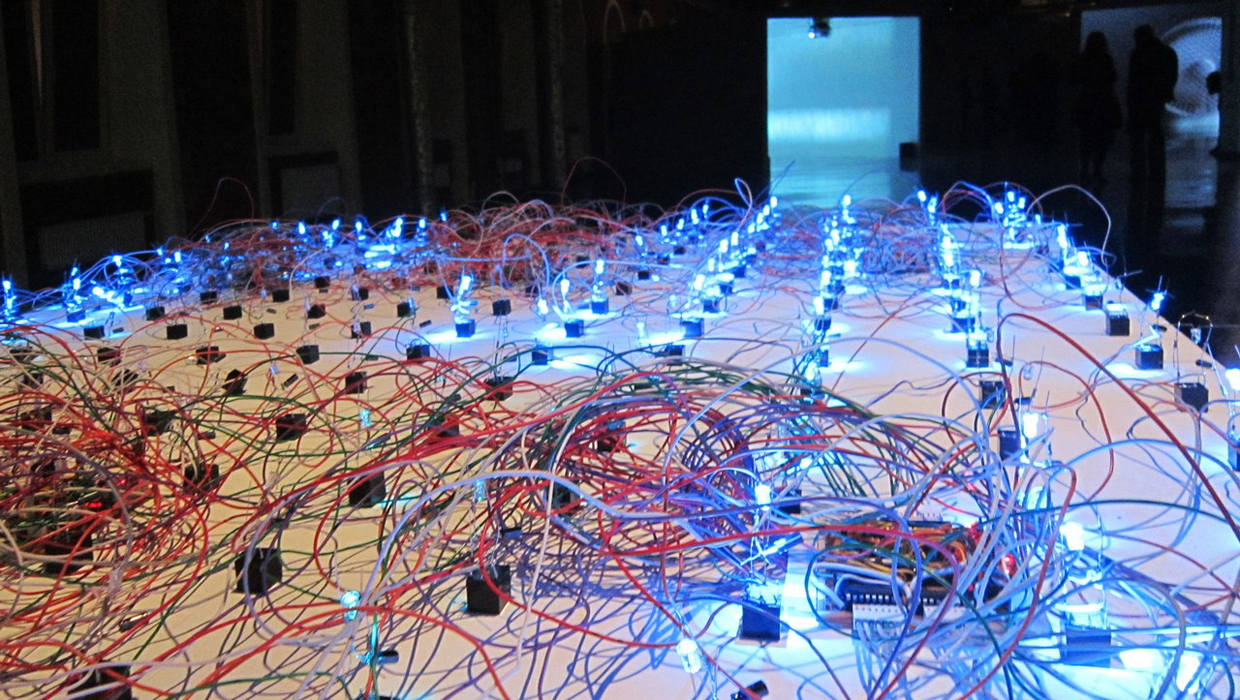

The material is illustrated with photographs and videos of the projects that were included in the CYFEST programs in different years. The images in the material’s layout include a photograph of Anna Frants and Marina Koldobskaya: Facebook of the National Center for Contemporary Art, North-Western Branch.